A father's fight | Social services breakdown

A voice on the other end of the phone told Johnny Smith his 3-year-old daughter had been badly injured in New York.

"I don't have a daughter in New York," Smith remembers thinking.

"I thought it was a joke," he said recently from his home, surrounded by farmland in rural Horry County.

It wasn't.

His daughter had been assaulted in almost-unimaginable ways, the full details of which Smith would not be told until weeks after that July 2008 call.

"When they told me my daughter had broken bones, I thought she had been hit by a car," Smith said. "I asked, 'Do I need to pick up my daughter?' They said 'No, she's in protective custody.'"

That call would trigger what has become a more than two-year-long battle to reclaim custody of his daughter, one that could force him into bankruptcy. Even though Smith did nothing wrong - his daughter's problem began when she was taken from his home - none of the agencies involved have blamed themselves for his predicament, with most officials saying they simply followed the law and standard procedures.

After weeks of examination by The Sun News that involved consulting police, medical and court records and peppering social services officials in New York and South Carolina with questions, Smith may be close to getting his daughter back sooner than he thought possible - though that is far from guaranteed.

The child's mother, Helen Prince, who was convicted on charges in connection with her daughter's attack, declined comment for this story.

Smith's fight also highlights the role poverty plays when social services officials decide if it's OK to allow a child to be raised in a home. A federal law, the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children, is at the heart of his case, just as it is for parents in similar struggles throughout the nation. The law is too inflexible, unnecessarily applied to parents and takes too long to wind its way to a resolution, akin to relying on the Pony Express in the age of the Internet, child advocates said.

"As it stands now, the system is extremely harmful to our kids," said Vivek S. Sankaran, a clinical assistant professor of law and director of the Child Advocacy Law Clinic at the University of Michigan Law School. He's one of the country's top ICPC legal experts.

"It has been good in that it allows us to get information. But it has denied [children] their opportunity - their right - to live with their own parent. There should be no difference in the decision-making process if a parent lives in state or out of state."

Two words - "financially fragile" - have proved to be a major obstacle in Smith's path.

The description of him was included in key ICPC documents drawn up by the S. C. Department of Social Services months after his daughter was attacked, and it has been used by New York Family Court decision-makers to keep his daughter in foster care almost 900 miles away from the home in which she spent most of her life.

DSS said other factors were also at play and that the agency doesn't punish poor parents.

"Being that I'm a country hick in Conway, they look at me like I'm a redneck," said the 36-year-old Smith. "In my life, all I wanted is to be left alone, raise my kids and do a little farming."

A legal labyrinth

He raises two kids from his first marriage and a stepson with his new wife. He owns outright a small house, four vehicles, including a tractor, and several acres of farmland. The fight to gain custody of his now 5-year-old daughter has depleted his savings, his 401(k) and his tax refund checks.

But because the ICPC placed unrivaled power in the hands of a few, he can't challenge the DSS findings. No S.C. judge can overturn or question the agency's rationale for helping keep his daughter away.

The ICPC was intended to provide out-of-state child protection agencies information about the environment of a home in which a child might be placed to determine if it would be a good, safe fit. Child welfare reformers were agitating to have the law significantly modified about the time Smith's daughter was being attacked.

"States have been trying to improve the system," said Carla Fultz, project manager for the American Public Human Services Association, which oversees the ICPC.

When it was first enacted by New York in 1950, the law "was never really based on a constitutional foundation," she said. "We are working on new policies now to try to address a lot of the issues" raised by reformers.

But Sankaran does not support the changes because they don't deal with its obvious constitutional problems. They also wouldn't address the challenges Smith has faced.

"The new ICPC would do nothing to change the outcome in Mr. Smith's situation," he said.

Other factors beyond Smith's control contributed to his plight. Inadequate resources and growing demand spurred by a struggling economy are stressing South Carolina's child protection apparatus. About $100 million in S.C. and federal funding was cut from the DSS budget during the first year Smith's daughter spent in a New York foster home.

About 135 DSS child welfare employees, who were trained to help families such as Smith's, have been laid off since Smith's daughter was attacked.

The agency's primary spokeswoman, lead attorney Virginia Williamson, had to take a three-day furlough amid responding to questions from The Sun News about his case.

Smith's plight has unfolded during a period in which the agency failed several measures on an examination by an oversight committee, including one that said the agency is supposed to maintain children safely in their homes "when possible and appropriate."

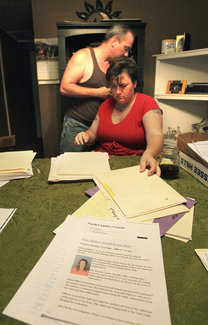

Disjointed coordination among multiple agencies was also at play. Tucked away in several tomato boxes, Smith keeps the information, court and police documents he has collected over the past two years from the Horry County Police Department, S.C. DSS, the Warren County Department of Social Services and their counterparts in Brunswick County, N.C.

"I'm convinced that DSS is handling a large percentage of cases correctly, but these cases ... frustrate me because there are multiple errors in all of them and you would think that something would be caught along the way in the process, and it's not," said Rep. Tracy Edge of North Myrtle Beach, who heads up the legislative committee which controls DSS funding. "When a case goes bad, it goes real, real bad. Hopefully they are few and far between."

DSS officials say they were simply following the law and said even a missed deadline did not affect the outcome. New York officials, who wouldn't speak specifically about Smith's case, gave similar responses about the process.

If New York and South Carolina officials are right - that they followed the law appropriately - then it is the law and the system in which it operates that has kept Smith from his daughter for more than two years and threatens to strip him of his parental rights because of the uncontested judgment of a DSS social worker.

Battered and lost

Before getting caught up in the system, Smith's daughter lived the first three years of her life with him and her mother, Helen Prince, Smith's former common-law wife, in a small trailer home on the farmland he owns with his siblings. His daughter liked trying to ride her pet goat.

After a strained separation period, Prince moved out in early April 2008, taking their daughter to live with a new boyfriend and his 12- and 15-year-old sons. Smith continued to pay for his daughter's day care and other bills as he tried to work out a private custody agreement with Prince.

A few of Prince's co-workers began to tell Smith they saw bite and other marks on his daughter and showed him photos of the injuries. During that time, Prince was only allowing Smith to see his daughter during occasional, short, supervised visits at the day care.

He went to the Horry County Police Department and told them about threats he said he received from Prince's family. He asked them to investigate what he thought were signs of child abuse. They referred him to DSS, he said.

So he took his allegations to the state's protective agency. Both agencies recently said they had no record of his complaints about his daughter's care on file.

Just nine days before Smith got the phone call from the Warren County Department of Social Services, he received a taunting MySpace.com message from Prince, telling Smith she left the state with their daughter, saying it was unlikely he'd be able to find them.

He didn't know she had taken his daughter to New York.

Or that the safest his daughter had been between the time he got the message from Prince and the phone call from Warren County was when, dressed in a shirt and diaper, she crossed busy Route 9 in Queensbury, N.Y., alone near an Outback Steakhouse and a Budget Inn.

Two motorists stopped for her and called authorities. That's when the system began to successfully protect her from further physical harm.

By that time, she had suffered broken bones, bruises and abrasions from sexual assaults, hemorrhages in both eyes and bald spots where hair had been yanked out. The injuries were so appalling that a powerful New York senator and prosecutor used her case to push for tougher child abuse statutes.

"There's no way [Prince] did not know about those injuries and that they should have been treated," Warren County Sheriff Bud York told the (N.Y.) Post Star newspaper at the time. "And then you also have the issue of her not watching the kid and letting her get out into traffic. She needs more than a misdemeanor."

Punished for nothing

All Smith wants is for his daughter to come back home.

He said a DSS official in Conway told him, "If I'm not a pedophile, it will be easy to get my daughter back."

He's not a pedophile, nor does he have a criminal history.

He still doesn't have his daughter.

Since that conversation more than two years ago, millions of Americans, including Smith, have been laid off. He has remarried and watched a grandmother die.

Prince was charged, convicted and spent eight months in a New York prison for her role in their daughter's abuse. She was freed early last year and moved to Brunswick County, where months later she was charged with similar offenses involving another man and his children.

When that man declined to show up in court as a primary witness against Prince, those charges were dismissed, according to Brunswick County court officials. Smith befriended the man because of the similarities of their cases and helped him move to a different state after the man said he was frightened by threats he received from members of Prince's family.

Brunswick County officials said they have received no reports of threats and have not said if they have followed up on those claims.

That means Prince can continue to fight for custody of the daughter who was so badly battered case workers in New York had to battle back tears when a judge read a list of her injuries aloud, according to the Post Star.

Since Smith's conversation with the DSS official who said it would be easy to get his daughter back, his daughter has likely learned to understand gender differences, how to follow three-step instructions and the definitions of words such as spoon and cat, among other speech and language development skills that usually occur between the ages of 3 and 5.

Or her development may have been slowed or compromised because of the extensive damage she sustained. Her father has not been given access to her full medical records and was rebuffed in his attempts to have her visit her Conway home during the holidays.

He has been allowed occasional, phone and supervised visits after 17-hour drives to New York. All of that and more happened during the two years Smith's daughter has been in a New York foster home, meaning she's spent 40 percent of her life in the child protective services system of a state a long drive up I-95 North.

"I want to know what I did wrong," Smith said he thought long ago.

He found out later it matters little that the answer to his question is: nothing.

Source: Myrtle Beach Sun News

Social Services breakdown | Records of father's concerns are spotty

Editor's note: This is the second in a six-part series of in-depth columns by columnist Issac J. Bailey to examine a Conway father's two-year struggle to bring his daughter home from a New York foster home.

Johnny Smith peered at the cell phone picture of his daughter taken by friends in early April 2008. The 3-year-old's jaw seemed swollen, and a reddish bruise marked the middle of her forehead.

The picture was snapped just weeks after the 3-year-old moved with her mother, Helen Prince, into a home with her new boyfriend and his 12- and 15-year-old sons.

His journey over the next two years illustrates the challenges faced by an increasingly stretched child protective services agency, as well as those experienced by a man with few financial resources to navigate that system to protect his daughter.

Smith, who had lived with Prince for nine years, saw his daughter infrequently in the first few weeks after Prince moved out. He continued to pay for day care costs but was allowed to pick her up only occasionally and was usually supervised by a day care worker during 15-minute visits, per Prince's instructions.

She had custody, and his name wasn't on his daughter's birth certificate. That oversight would complicate his quest and eventually led to a paternity test that verified his fatherhood.

Prince did not respond to messages for comment.

Smith and Prince were working with a counselor to establish a visitation schedule, but when those talks broke down, he consulted two lawyers. One said it would take $3,500 to begin legal custody proceedings; the other said it would cost $4,600. The price was steep for his modest income, but he planned to move ahead with the process.

When friends told him that the boys his daughter now lived with had beaten her with a 2-by-4, he said he took his concerns about his daughter and reports of threats by Prince's family to Horry County police.

An officer told Smith it was a family matter and referred him to the S.C. Department of Social Services office in Conway, he said. But records of what he reported to authorities are scarce.

"It can not be verified that he came in to speak about his children," said Sgt. Robert Kegler, Horry County police spokesman. "I spoke with [the officer Smith said he met], who doesn't recollect him from two years ago. Law enforcement and DSS work together in cases of abuse. We begin with an initial report with the specific allegations of the abuse."

An incident report dated April 10, 2008, does document Smith's complaints that he had been threatened by Prince's family. An officer wrote that "all parties have been advised that this matter is a family court matter." Smith said it was then he also mentioned the suspected abuse.

Smith said he went to DSS a week later after a day care worker said she spotted bite marks on his daughter. He remembers being taken into Room 18 at the Conway DSS office. A DSS worker jotted down notes, took names and asked what Smith needed the agency to do, he said.

"Please, just check on my daughter because these pictures frighten me," he said he told the case worker.

No record here

DSS spokeswoman Virginia Williamson said her agency has no record of his attempts to report his allegations.

Horry County DSS "found no information about Mr. Smith coming to DSS to make this report," Williamson said. "It may be that the staff member he talked to is no longer with the agency. A worker who does not record and follow up on a complaint like this one would have committed a serious violation of policy. Unfortunately, we cannot identify who may have been involved. ... If someone who is working in our office failed to follow up on his complaint, we want to know who it is."

The DSS worker told Smith they'd check into his claims, he said. He had no way of knowing the budget-constrained Conway staff would receive 1,754 similar complaints about abuse that fiscal year, only 823 of which fell under DSS jurisdiction.

Of those that were investigated, 28 percent were "indicated," DSS lingo signaling there was evidence "that abuse or neglect had occurred or that there was a substantial risk of abuse or neglect."

He had no way of knowing that vindictive husbands, wives, neighbors and family members help overload the DSS abuse hot line with false claims, forcing workers to spend time chasing phantoms in the midst of trying to identify real abuse and abusers.

Statewide in 2009, roughly 175 DSS case workers investigated 18,000 claims of abuse - 7,000 of which turned up evidence of abuse or neglect.

The department fielded another 10,000 complaints that were not within its legal powers to examine - DSS can't investigate claims that your neighbor committed abuse while trying to discipline your child while she played in your neighbor's yard, for example - this during a fiscal year in which the General Assembly enacted across-the-board cuts that reduced the agency's budget by $100 million through the loss of state and matching federal funds.

Smith gave DSS the address where his daughter was living, just as an official had asked. He said he visited the agency again two weeks later.

"They told me they couldn't follow up on it because it was a bad physical address," Smith said.

Prince's boyfriend owned a small landscaping business. He ran it out of the home where they stayed. That officially made it a business address.

DSS can't examine claims of child abuse at such locations and he needed to take his claims to the police, Smith said he was told.

"DSS would not refuse to follow up on a child abuse report/complaint simply because the reporter was unable to provide a residential address versus a business address," Williamson said. "In fact, DSS would open an investigation even without a complete address."

Dire situation

Smith felt stuck as he grew more concerned about his daughter. He would find out later the danger facing his daughter was far worse than what he feared.

According to court documents, the 12-year-old and 15-year-old told police in New York they had begun sexually abusing and assaulting her in the house Smith said he urged Horry County police and DSS to investigate.

In July 2009, South Carolina failed seven benchmarks on a federal report assessing its child welfare system, including Safety Outcome 1 - "Children are, first and foremost, protected from abuse and neglect."

The "2010 Kids Count: A South Carolina Perspective" ranked the state 45th of 50 states in child welfare, showing no improvement over the past 20 years.

"Being ranked 45th continually for the past two decades causes serious concern for the next generation of children," Sue Williams, chief executive officer of The Children's Trust of South Carolina, said when the study was released. "As a state we must begin to have a concentrated focus on the well-being of our children in a holistic manner."

Weeks after Smith went to DSS, he received a cryptic MySpace.com message from Prince. It was sent July 19, 2008, 10 days before his daughter would be found alone on Route 9 in Warren County, N.Y.

"Im not in the state of south carolina any more good luck finding me ... BYE," it read.

After asking everyone he knew about her whereabouts, he went back to the Horry County police department.

There was nothing they could do because Prince had legal custody of his daughter, Smith said he was told.

"It is going to depend on the family court order and what it says," Kegler said.

"I was thinking I was never going to see my daughter again," Smith said.

He would. When he did, he knew things would never be the same.

Source: Myrtle Beach Sun News

Social Services Breakdown | System tears dad from his daughter

Girl kept in foster home despite abuse under mom's care

Editor's note: This is the third in a six-part series of in-depth columns by columnist Issac J. Bailey to examine a Conway father's two-year struggle to bring his daughter home from a New York foster home.

Johnny Smith cried when he first saw the bald spots where hair had been yanked from his daughter's head.

He cried some more. His mother joined him.

"We couldn't believe what all they done to her, all of the damage," Smith said. "All we did was hug her then not let her go until it was time to go."

It was Sept. 29, 2008 - more than two months after he'd gotten a call from New York saying the 3-year-old had been found wandering alone in a diaper and T-shirt on a busy street after she and her mother moved there, along with her mother's boyfriend and his 12- and 15-year-old sons.

The mother did not respond to several attempts to get her comments on the case.

A Warren County, N.Y., Social Services official told Smith not to come to New York any sooner because he would not be allowed to see his daughter.

"She almost didn't recognize me," he said. "I cried the first 30 minutes I seen her."

He was also disturbed by the bruises on her face and jaw, injuries described in medical and court documents as being "in a fan like pattern."

And the "anterior neck bruising and abrasions extending from ear to ear."

"She was black and blue," Smith said.

An array of harm

There were other injuries, tears in sensitive areas and broken bones. Some of the broken bones had begun mending themselves while others were broken, meaning the toddler had sustained untreated abuse over a period of weeks.

Her mother told New York police she had been giving her daughter "large amounts of Benadryl for no apparent medical reason," according to court documents.

Wesley Smith, the father of the only child who died the past decade while in the care or under the supervision of the Horry County Department of Social Services office, was sentenced to 20 years in prison in part because the prosecution argued he used medicine on his young daughter in a similar fashion, saying he "chemically restrained" her.

That 2004 Smith case - and others in which a child dies and generates white-hot public scrutiny of child protective services - have caused DSS and other like agencies to err on the side of being overly cautious. That, in turn, has helped to overload the foster care system with children whose outcomes would be better if they were left or allowed to return home, according to research by the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform.

In such an atmosphere, each family imperfection could become an indictment. Under the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children law, when those indictments are made by a case worker, they can quickly become the equivalent of uncontested convictions.

The saga of Johnny Smith's daughter's began when she moved with her mother to a Myrtle Beach-area house they she shared with her boyfriend and his sons. According to court documents, they admitted the crimes.

The 15-year-old was charged, but the charges were dismissed because the confessions came during interrogations without the boys' father present.

Their rights protected them from being punished.

Smith's rights haven't been enough to reunite him with his daughter.

During that Sept. 29 visit, he was staring at his worst nightmare. The 3-year-old's language development had reverted to baby talk and she was wearing diapers again, a step back from the pull-ups she had begun wearing.

He hadn't been able to protect his daughter from the abuse he had suspected was occurring.

He hadn't been able to hold his family together and wouldn't be able to rock his daughter to sleep that night as he did when she was his baby.

So he held her for most of the hour-long visit.

"When a child is that small, watching them sleep is like Christmas to me," Smith said. "I enjoy a happy child."

Having to leave

His daughter wasn't happy that day, a day he was allowed to see her only in the presence of Warren County, N.Y., social services officials. She quietly asked Smith's new wife, Cheryl, if she "could go back to daddy Johnny's house."

And he wouldn't be happy at the end of the visit.

Because he had to leave her.

Because even though he and a few family members had driven 17 hours to New York from Conway - even though he was her father, had fed and clothed and provided her shelter - he didn't have the right to take her back to the place she spent most of her young life.

Because even though her mother wasn't available - she had been charged and would be convicted in connection with the multiple attacks his daughter endured - he had to leave her there with strangers.

Because even though he had no criminal record and had tried to involve two agencies to investigate what he believed were signs of abuse, he wouldn't be allowed to walk out of that room with his daughter.

Social services officials and the laws had determined it was in his daughter's best interests that the ICPC process decide if he was a fit parent, no matter that he had done nothing to forfeit his rights.

Nor did it matter that Smith years earlier was declared fit enough during bitter court proceedings to end his first marriage to be granted full custody of his two oldest children.

"To see your child like that and not be able to take her home ... " his voice cracked, then faded. "All I felt like when I was leaving was like a piece of me was missing. And I ain't been right since."

Obstacle of poverty

The obstacles he faces in fighting for his daughter are the same as those faced by others in a similar financial situation trying to navigate an unfamiliar government system.

His bank account wasn't flush enough and his home wasn't big enough to avoid the extra scrutiny placed upon those in poverty.

He was just Johnny Hudson Smith, born on a farm in a rural part of one of the nation's poorest, most rural states.

The child poverty rate in South Carolina has increased 16 percent during the past decade, with 22 percent of its children living below the poverty line, according to the 2010 Kids Count Data Book. The state's double-digit unemployment rate threatens to send the rate even higher.

"Poor people are treated differently in terms of the child welfare system in that poor people are almost the only people in that system," said Richard Wexler of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform. "Middle-class families rarely get caught in the net."

As he was leaving that first one-hour supervised visit, Smith wondered if his daughter would begin to view him as he once viewed his father - as only a distant and infrequent presence in his life.

His father, Bobby Wayne Smith, farmed the 123 acres that's been in the family for almost a century. As a young boy, Johnny Smith helped him take care of animals and did other chores.

But when the farm industry changed in the 1980s it became harder to make ends meet. His father bought new equipment and trucks and switched to construction. He helped clear the lots where Deerfield Plantation now stands.

"It was pretty good for a while, then everything slowed down," Smith said. "Then he started driving a semi-truck. About the only time I'd seen him was about bedtime. He worked seven days a week, 360 days a year, and holidays were no exception. He did about like what I'm doing, to do what he had to for his family to live. At the time I didn't understand it, but I do now."

He's afraid his daughter won't understand why he left her in New York.

"I know how it hurt me when my daddy wasn't around me," he said.

Source: Myrtle Beach Sun News

Social service breakdown | Father fights a tangle of bureaucracry

Editor's note: This is the fourth in a six-part series of in-depth columns by columnist Issac J. Bailey to examine a Conway father's two-year struggle to bring his daughter home from a New York foster home.

The day more than two years ago Johnny Smith received a call from New York telling him his daughter had been badly hurt, he was also told not to bother trying to see her until a hearing two months later.

New York officials were moving forward with the use of a federal law called the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children, which meant his right to care for his injured daughter was no longer his.

"They said she was in protective custody and I wouldn't be able to see her because of the trauma," Smith said.

The child's mother did not respond to several attempts to get her comments on the case.

ICPC was enacted to provide a uniform standard for placement of children in foster care across state lines, said Vivek S. Sankaran, director of the Child Advocacy Law Clinic at the University of Michigan Law School, who is considered one of the country's top ICPC experts. The intent was a good one and the law can provide good information for child protective services officials to make informed decisions about home placements, he said.

But he and other national child care advocates and reformers said cases such as Smith's highlight the need to reform the ICPC and that more parents need to be told that biological ties or raising children for years or even from birth are not bulwarks against the legal obstacles ICPC has presented Smith.

"This is a huge problem that there are kids in foster care who have families that are willing and able to take care of them," Sankaran said. "This problem is increasing in scope. Not only are we hurting kids, we are keeping kids in foster care and it is costing us money. I am becoming more convinced that federal oversight of this is the only way this will be solved."

South Carolina and New York officials said once an ICPC request is denied by another state, they cannot make the out-of-state placement. In Smith's case, that means the finding of an Horry County DSS case worker guaranteed New York would not allow his daughter to come home.

Child advocates have compiled a list of such cases occurring throughout the country:

A 1-year-old girl was removed from her mother in New York and sent to live with relatives in South Carolina, which the state initially approved. The mother's parental rights were terminated and New York asked South Carolina to do another home study as part of adoption proceedings.

"This time ... the person who had been caring for the child was originally rejected as too poor and not owning a car," said Judith Waksberg, director of the Appeals Unit of the Legal Aid Society in New York. "Later, South Carolina added that this relative had had an indicated neglect case, although the validity of that charge was disputed and none of the children in the home, including this child, were ever removed. Although other relatives of the child came forward and volunteered to care for her, South Carolina rejected them as well. One was rejected for insufficient income and high debt.

"...Apparently South Carolina thought it would be better for this child to be sent off to New York where she had no family to be put in the care of an as yet unidentified foster parent than to allow her to remain in South Carolina where most of her family, including her siblings, were," Waksberg said.

DSS officials said they don't deny placement or remove children from their homes because of poverty.

An Alabama mother who lost her children because of neglect was awaiting the return of her children. She had completed all the services the court required, obtained adequate housing and moved closer to family members, where she'd have more support. In the fall of 2006, a court ordered an "expedited" ICPC package. After a delay, a court issued an order directing the social services agency to forward the ICPC within 20 days.

Alabama received the package on Feb. 20, 2007, where it languished for so long a court intervened, but to no avail; the mother was killed in a car accident waiting for the process to be completed, before she could see her children again.

"I have no idea how often this is happening, but I suspect it is much higher than we think," said Sankaran, who kept some of the stories above on file. "I say this based on horror stories I hear from practicing attorneys all across the country. But it's hard to get stats on this. I used to collect the stories I gathered on this issue but stopped because there were too many."

Between July 1, 2009, and June 30 of this year, South Carolina received 1,329 ICPC requests from various states. Of those, 607 have been approved, 283 have been denied, and the others are under review.

Statute argued

Sankaran wants to modify the law and add a judicial process in which parents can challenge the findings of an ICPC home study denial.

The law should not apply to biological parents, he said. And a state should have the option of making the placement even in face of a denial from another state, something he believes should immediately occur in the Smith case.

The Court of Appeals in Washington State ruled in August that ICPC should not apply to parental placements, arguing the statute is too liberally applied.

The ruling does not apply nationally but does help in the push to reform ICPC, Sankaran said.

Warren County, N.Y.'s decision to use ICPC pushed Smith into a legal rabbit hole from which he has not yet been able to emerge.

After Smith was removed from any cloud of suspicion, Warren County social services officials requested that South Carolina conduct a home study to determine if his home would be a good, safe fit for his daughter's return.

That request did not go directly to the DSS office in Horry County. In a world in which a library of information can be sent around the world and back within a matter of seconds, the request went through a several-months-long process to comply with ICPC.

First the request from Warren County went to the New York state office. From there, it traveled to the South Carolina state DSS office, which received it on Sept. 9, 2008. The state office then sent it to Horry County, which faxed it back to Columbia on Nov. 5. The Columbia office sent it back to the New York state office Jan. 27, 2009.

That four-and-a-half month timeframe was longer than the compact's 60-day requirement. And it doesn't include the time it took for the request to go between Warren County and the New York state office because officials there declined to respond to specific questions about the case.

That slow process might have been necessary when ICPC was enacted decades ago, before computers, faxes and email, said Don M. Hodgdon, a Connecticut attorney who specializes in ICPC cases.

It no longer is, he said, particularly if a parent desperate to have his child returned home is willing to waive privacy rules to shorten the process.

"You can call my human resources department to get my job [status], you can call the local police department, you can call town hall to see if I pay my taxes every year," he said.

And there are no uniform standards about what determines a parent's fitness, Hodgdon said. "One of the oldest fundamental rights in this country is the right to raise our children," he said. "We also have the right to due process of law."

Home study standards

SC. case workers use a standard 16-question form that requires both factual and subjective answers.

The new ICPC law will make the process more standard, said Anita Light, director of the American Public Human Services Association, which oversees ICPC. It will have expanded mediation, remedial and litigation options but will still apply to parents. The new law has been adopted by 12 states, but not South Carolina, which is waiting to make sure the updated law is in its final version. Thirty-five must adopt it before it becomes the nationwide standard.

"Whenever the state has to step in for child protective reasons, it really steps in almost as a parent," Light said. "They will act in the best interest of the child. That will continue under the new ICPC. This is a good law. There aren't any perfect laws."

In Smith's case, his mother helped him buy plane tickets to New York and sometimes buys things for her grandchildren. In the ICPC report, that was presented as evidence that Smith wasn't financially capable of taking care of his daughter.

"DSS is trying to deny Mr. Smith custody because he is poor. Period," said Richard Wexler of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform. "The fact that his mother is helping should be viewed as a strength, one more person who loves and cares for this child. Does DSS think 'Extreme Makeover' will come by for every family in this situation?"

After waiting to hear something weeks after a New York judge ordered the ICPC home study, Smith visited the DSS office in Conway to find out why the process was taking so long. The case worker, Cathy Gowans, said she had other cases to clear first. Gowans averages between 100 to 120 ICPC studies annually, in addition to four in-state home studies every month and seven or eight other ICPC visits she must also complete.

"She must document those visits, do other follow-ups needed based on what is going on in the home, and quarterly prepare reports on the family to send back to the sending state," said Virginia Williamson, DSS spokeswoman and lead attorney. "If there are changes that require attention from the sending state, she prepares earlier or more frequent reports."

Gowans assists monthly with foster parent orientation during business and after hours and has been required to take five furlough days since 2008, like other DSS workers because of steep budget cuts.

"Her workload can vary because most of it depends on how many requests for home studies come in at any given time," Williamson said. "It is manageable."

Gowans also had to adjust to frequent upheaval in the ranks of her supervisors. The Horry County DSS office has had five people head up the office since Smith's daughter was taken into New York protective custody in July 2008. It currently has an interim director.

A second home study request from New York was received by South Carolina on April 9, 2009, and sent back to New York by June 8, 2009. It didn't reach Smith's attorney until the day of court.

"The judge was reading it for the first time during the hearing, and my lawyer hadn't had a chance to read it yet," Smith said.

A third study was ordered by a New York judge on May 3 of this year. S.C. DSS said it received that request on July 27 and an Horry County case worker went to the Smith home on Aug. 9.

Smith is afraid the results won't make it back to Warren County in time for a third permanency hearing, now scheduled for Oct. 27

He remains baffled by the reasons given in the first two Interstate Compact studies by a case worker who declared him a father unfit to care for his daughter.

He wants to know why DSS deemed him "financially fragile" in key documents that kept his daughter away while another government agency said his household income was so high his children would be kicked off Medicaid.

Source: Myrtle Beach Sun News

Dad gagged in defense of household

Social worker's word is final under federal law

Editor's note: This is the fifth in a six-part series of in-depth columns by columnist Issac J. Bailey to examine a Conway father's two-year struggle to bring his daughter home from a New York foster home.

It took three months from the time Johnny Smith learned his 3-year-old daughter had been found wandering alone on a busy New York highway until a social worker arrived at his rural Horry County farm to investigate whether it was safe for the child to return to where she'd lived most of her life.

Because the case involved two states it comes under the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children law. And because of the way South Carolina and New York interpret that law, Smith could not challenge a social worker's decision, once it was approved by her supervisor.

In non-ICPC cases, DSS has to prove its findings before a Family Court judge.

That's why a family that DSS declared financially unable to care for another child has been forced to deplete most of its meager resources to reclaim its youngest member - with no assistance from the social services agencies in New York or South Carolina, a violation of other federal statutes, according to the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform.

"Effectively, South Carolina has terminated [Smith's] parental rights," said Vivek S. Sankaran, director of the Child Advocacy Law Clinic at the University of Michigan Law School. "Their decision is prohibiting New York from taking any action to place the child with her father, and they themselves are admitting that they have no appeals process.

"Depriving a presumptively fit parent of custodial rights to his child without a hearing is a clear violation of the Constitution."

The mother of the child did not respond to several attempts to get her comments on the case.

The state's case

Had there been an ICPC appeals process in South Carolina, the social worker, Cathy Best Gowans, would have taken her arguments and evidence before a Family Court judge on the second floor of the Horry County Courthouse in Conway. The county's DSS attorney would walk her through testimony to convince the judge that Smith's home was not suitable for his now 5-year-old daughter.

Smith or an attorney representing him would have the chance to cross-examine and present counterarguments. The opposing sides would likely have touched on the following points before a judge ruled:

Gowans would have said she visited the Smith home on Oct. 27, 2008, a 1962 double-wide Fleetwood mobile home he moved into 10 years ago. It had four bedrooms, a bathroom, a kitchen, and living and laundry rooms with central heat and air, major appliances and city water.

It is located in rural Horry County, roughly 10 to 15 minutes from the nearest medical facility, Conway Medical Center.

She would have said a criminal background, Central Registry and sex offender checks performed on Smith turned up only a misdemeanor charge of criminal domestic violence from long ago for which he was found not guilty.

She would have said he completed the 11th grade at Conway High School, dropped out and married his girlfriend because she got pregnant, divorced in 2002 and was granted custody of his two children from that marriage. She would also have reported that he'd worked for Altman Tractor for 11 years, and said he has never had a substance abuse problem.

The judge likely would have learned that Smith takes high blood pressure medication, and the two children from his first marriage take medication for ADHD. He earns $12.50 an hour, his son receives $623 in Social Security benefits because of his ADHD, his kids receive Medicaid, his mother helps him financially, and he made a few dollars too many to qualify for food stamps.

His monthly expenses include $236 for utilities, $186 for phone service, $123 for auto insurance, and he has two maxed out credit cards.

Those are the primary facts Gowans included in the initial ICPC report.

"Mr. Smith reported that he has been working diligently remodeling his home," she would have testified. "However, the inside of the home was observed to be extremely cluttered with debris. The outside was also poorly maintained with the two dogs and the goat. Mr. Smith further admits that his mother assists the family financially, which indicates he is unable to support another child. Due to Mr. Smith's admission [that his former common-law wife's associates] are driving by his home disrupting the family there is a concern if placed in this home if Mr. Smith can protect the child from further victimization."

In a follow-up ICPC report seven months later, Gowans again denied Smith's petition for custody. In that report she wrote: "the inside of the home observed with clothes and trash on the floors, over-filled trash bags, unmade beds, bags of trash and clutter in the bathroom." She also noted school disciplinary problems involving Smith's stepson.

"This family is financially fragile and there are concerns ... in regards to the other children in the home," Gowans concluded. "We are concerned that these children requires [sic] so much attention and special care that placing another child into this home may be detrimental to this already strained family unit. We do not recommend placement of child ... in the home of her father, Johnny Smith."

The father's case

If he'd had the chance, Smith would have countered this way:

He would have said his daughter lived the first three years of her life in the home Gowans called cluttered, that it was in that situation temporarily because of the renovations and the closed recycling center, and that the child's injuries occurred only after she was taken out of that home by her mother.

He would have said his modest home is paid for, as are 123 acres of farmland he shares with his siblings.

He would have told the judge that he is handy with engine repair, something he continues to do for Altman Tractor on a contract basis after being laid off, and that he has four older model vehicles, including a farm tractor, all paid for.

He would have said his mother does not financially support him - that he has held a job since the age of 14 - but helped him buy an airplane ticket when he was told at the last minute that Warren County was about to hold a hearing in an attempt to strip away his parental rights.

His mother would have testified that she does not support her son, because she doesn't have to, that she provides help in the way most grandmothers typically do and helped Smith in a pinch with the plane tickets to New York. She would say Gowans never called to verify her conclusions before sending the denial to New York.

He would have put Terry Smith and Lynn Hucks of the Wraps Behavior Intervention Program at Whittemore Park Middle and Conway High schools on the witness stand, who likely would have said, "I can confirm that Mr. Smith has been very assertive in his efforts to improve his family's overall mental, physical and financial conditions and continues to work alongside all team members who assist him in his efforts to reach his ultimate goal of family stability," as they wrote in a letter on Smith's behalf.

He could have argued successfully against even the mention of the domestic violence charge of long ago for which he was found not guilty. It only shows up on criminal background checks because in South Carolina the defendant must pay to have charges, even unfair ones, expunged, a stipulation of which Smith was unaware.

"We ain't got a lot to spare, but we take 'em [the kids] to the movies or something nice once a week," Smith would have said.

And he would have testified that DSS did not take into account that without a mortgage and car payments, the family's farm produces more than enough food to help them fill in financial gaps, as does his handiness. He used wood from a tree felled by a hurricane in his home's renovations. His farm produces baskets and bushels of peppers and corn and onions and cantaloupes, cucumbers, okra, herbs - and 3 acres of sweet potatoes - some of which they sell, some they eat or stow away.

"They said my house was trash because it was an old mobile home," Smith said. "I may not live in the Hilton, but it's paid for. Damn, I'm trying, man. I can't believe these people say I ain't trying."

But Smith wasn't allowed to do any of that because South Carolina has no ICPC appeals process. Even under a new version of the ICPC, which has been adopted by 12 states (but needs 35 states before ratification), that might not change. South Carolina can make the change on its own.

Because of the current ICPC interpretation and implementation, Smith has taken multiple 17- to 23-hour road trips to New York to see his daughter for an hour or two at a time.

Because of that, the roughly $10,000 he had in savings has been depleted. And $7,300 he had in a 401(k) is gone, 20 percent of which was taken away because of an early withdrawal penalty.

And his tax refund checks have been used to pay a $295-an-hour lawyer, the least-expensive one in New York he could find. He had to send an $800 check to a lawyer instead of using the money for his older daughter's 14th birthday.

"I was ashamed I couldn't get her the new radio and girly jewelry she wanted," Smith said.

Because of how the ICPC is playing out in his case, New York has given notice that it may pursue $23,000 in child support payments it says Smith owes for just six months of his daughter's more than two-year stay in foster care - even though he's begged and pleaded to let her come home since finding out she had been assaulted.

Because of that, he is facing another $1,200 trip to New York for an Oct. 27 hearing that could determine his daughter's future. That doesn't include another $6,000 in lawyers' fees he expects to have to pay. His retainer ran out in May.

If the case drags on much longer, he may be forced to take out a mortgage on his land. He's contemplated selling his tractor.

"I'm almost bankrupt because of this," Smith said. "And I still have to pay more money for something I didn't even do."

But even more frightening is the possibility that because of the way the interstate law is being used in his case, his former common-law-wife might be granted custody even though she spent eight months in a New York prison for the crimes committed against his daughter.

Source: Myrtle Beach Sun News

Family hopeful for girl's return

S.C. backs father's case; it's up to N.Y.

Editor's note: This is the last in a six-part series of in-depth columns by columnist Issac J. Bailey to examine a Conway father's two-year struggle to bring his daughter home from a New York foster home.

Late on Oct. 25, Johnny Smith, his wife, Cheryl, and maybe his mother, a brother and sister-in-law plan to load themselves into a couple of vehicles and head north.

They will travel almost 900 miles, stop maybe six times to refill the gas tank and eat over the course of the 17-plus-hour trek they've made seven times - U.S. Airways got them there twice; three of the road trips were to be there for operations Smith's daughter underwent to heal injuries sustained when she was abused. They will eventually end up on State Route 9 in Warren County, N.Y., the road where in July 2008 Smith's then-3-year-old daughter was found by motorists wandering alone in a shirt and diaper after being attacked by caretakers when she was in the care of her mother.

The mother did not respond to several attempts to get her comments on the case.

It is there Smith's case is scheduled to be heard Oct. 27 before a Family Court judge in the Warren County Municipal Center.

They will walk into the courtroom knowing something has finally changed in their favor. After twice denying her return, the S.C. Department of Social Services has reversed itself and now approves of Smith's daughter coming home. The denials are always upheld by New York child protective services officials because of the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children, a law designed to govern such cases when they involve two or more states.

"South Carolina did studies at the request of New York in 2008, 2009 and 2010," said Virginia Williamson, the lead attorney and spokeswoman for DSS. "Mr. Smith and his family have made changes since 2009. Based on those changes, we have been able to recommend the placement in 2010. We are very happy with this result and hope for a favorable disposition by the State of New York."

There's also a chance Smith may not have to wait for that Oct. 27 permanency hearing.

"If an ICPC placement out of New York is approved, the placement can be made, regardless of the timing of the next permanency hearing," said Pat Cantiello of the New York State Office of Children and Family Services, who was not speaking directly about Smith's case because the office declined Smith's offer to waive his confidentiality.

But just as Smith's financial status became an issue early in his struggle to regain his daughter, it remains one. He's spent months scraping together enough money to pay for a New York lawyer to represent him in court in October, as well as for his travel, lodging and other expenses. It would be a strain to come up with more money to pay the lawyer's fees that might be necessary to petition New York to not delay his daughter's potential homecoming until late October.

And even though South Carolina has removed the primary hurdle, its approval provides no guarantees. The way the ICPC is interpreted by New York and South Carolina, New York had to uphold South Carolina's two denials but is under no obligation to uphold South Carolina's approval, during the planned permanency hearing or before. New York earlier began proceedings to have Smith's parental rights terminated, and the state retains the right to move forward with them again.

Two years ago, the foster mother who has been taking care of Smith's daughter told him if he was unable to regain custody that she would be in a good, safe home. Her identity would also be changed, Smith said he was later told.

"To be given a whole new name and Social Security number, that hurt my heart when they said that could happen," Smith said.

Uncertainties remain

If New York does allow Smith's daughter to come home, South Carolina will be required to monitor and help the family. During Smith's more than two-year fight, neither New York nor South Carolina offered Smith assistance, financial or otherwise.

Another complication is how New York officials will view Helen Prince, Smith's former common-law wife and mother of his now 5-year-old daughter. Prince served eight months of a one-year sentence in a New York jail for child endangerment charges for the abuse suffered by her daughter. She was released early last year.

Prince, who now lives in Brunswick County, N.C. is also trying to regain custody. Brunswick County's Department of Social Services would first have to approve such a placement.

The Family Court judge in New York could decide to grant custody to either Prince or Smith and supervised or unsupervised visits to the other parent.

The factors surrounding that possibility create more concerns for Smith.

Months after being released from the New York prison, Prince and her 14-year-old son faced charges in Brunswick County related to the sexual abuse and neglect of a young child under their care. Her son's case was being handled in juvenile court. Prince's charges were being handled in criminal court and were initiated by the father of the young child. When he did not show up for a court hearing, those charges were dismissed.

"Since taking out those charges [he] has discontinued contact with the DA's Office, Juvenile Services, and even [his 14-year-old stepson], so I was not surprised that he failed to show up for court," said Meredith Everhart, assistant district attorney for Brunswick County.

Visitation worries

According to news accounts in the (New York) Post Star in 2008, Prince told investigators she noticed injuries to her then 3-year-old daughter but was told by the 15-year-old son of her boyfriend they happened when "she was in the bathroom trying to get out of her bathing suit, [and] she fell."

Her lawyer at the time, Gerry Amedio, told The PostStar.com said she did not mean to harm her daughter. She "just had a lot on her plate" while trying to work, care for the children and find a home while her boyfriend was still in South Carolina working.

Prince has not responded to calls and messages for comments. Through social networking messages, Prince told friends and associates that she was not to blame, because her daughter never complained about being hurt.

"I think she's still in denial," Smith said.

And that's what concerns him about potential court-ordered visitation rights.

His daughter required surgery, the removal of her tonsils, a two-night stay in the hospital and ongoing psychiatric treatment for the injuries she sustained over a period of weeks while in her mother's care.

Still, his biggest fear remains the one he's been battling since 2008. He's afraid if he won't get his daughter back, she'll forget him.

He's afraid he'll miss more of what has already been missing from his life, like the way girls his daughter's age happily jump into their father's lap for no reason and without warning, the way they bring home handmade trinkets from camp, the way they cry and hold their father's hand a little tighter while walking into school for the first time, the way they ride a pet goat around the yard, as she did in the days before she left with her mother.

"That was the last child that I had," Smith said. "And girls are kind of rare in my family. I don't know exactly how to say it, but I was more or less compelled to see that she come back ... so she wouldn't forget where she came from."

That's why he's kept buying her clothes - two sizes too big to keep up with her growth - and had kept them neatly in her room until he shipped them off, along with school supplies, to her New York foster home.

That's why he said that even though he's hit "brick wall after brick wall" he won't stop fighting until all options have exhausted. If he fails, he said, he wants his daughter to know he did everything he could, that he didn't abandon her, that he tried to protect her.

Source: Myrtle Beach Sun News

The publicity associated with this series of articles has had an effect on the case. Father Johnny Smith will soon get his daughter back.

Father: Wait drags on for daughter

LAKE GEORGE -- Johnny Smith became separated from his then-3-year-old daughter in March 2008. Then he learned of allegations she had been beaten, abused and sexually assaulted.

He learned details over time, starting with a call he received while at work in South Carolina, where he lives. Over the next two years, Smith waged a legal battle in two states to gain custody of the child, who had been allegedly abused while in the company of two young sons of her mother's live-in boyfriend in Warren County.

It was that battle that brought Smith to Warren County Family Court on Wednesday when a judge adjourned a hearing to Friday -- but not before it became evident Smith would finally gain custody of his daughter, now 5 and in foster care.

Neither the child's mother, attorney for the girl nor a Warren County attorney expressed opposition.

But for Smith, 36, an agonizing question remains -- when?

"I'm happy with it, but I'm skeptical something is going to fall through the cracks again ," Smith said after the hearing. "It's been two years and whenever I come up, they find something to prolong it ... it has just been a living hell for me."

His daughter's ordeal came to light when the child's mother, then-33-year Helen Prince, was charged with child endangerment. On July 19, 2008, the girl was found on Route 9 outside a Queensbury motel where she'd been staying. Police said the woman had left her daughter in the care of two boys, ages 15 and 12, every day for a week.

The abuse inflicted on the child led to injuries that included broken bones, hemorrhages in her eyes, places where hair had been pulled out and bruising from sexual assaults, according to the Sun-News newspaper Myrtle Beach, S.C., which has reported extensively on the case. The disposition of the charges against the 15-year-old were not immediately available.

Neither Prince nor her attorney commented when approached by the Times Union Wednesday

Smith said the girl's mother, his former common-law wife, took the child away in March 2009 to live with her boyfriend down South. He said the two later moved to Warren County to be closer to the boyfriend's Vermont family.

Despite allegations that later surfaced, Smith could not gain custody of his child. He said that was largely due to the federal Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children, which handles such cases when more than one state is involved. Smith, who does building restoration work, was at one point unemployed. He said the interstate compact deemed him "financially fragile" in findings he contends included a multitude of inaccuracies.

In the meantime, he was without his daughter. He said he has since made the 850-mile, 15-hour trip every six months to attend hearings to win custody of the child.

On Wednesday his Schenectady-based attorney, Mark Gaylord, told Family Court Judge J. Timothy Breen that his client has already made arrangements with a rape crisis center in Conway, S.C. and has enrolled the child for counseling. Smith said he is ready for the child to begin school Monday in South Carolina.

The mother's attorney, Nellie R. Halloran, expressed no opposition to Smith having custody. H. Bartlett McGee, an attorney for Warren County Social Services, also told the judge he did not oppose the girl going to Smith. But the mother's lawyer said her client consented to the father's custody "with terms," an indication the mother would want visiting rights. And McGee said the transition for the girl, who is therapy in New York, should not be abrupt. He told the judge his agency was simply following the law in the legal process, despite media coverage he considered critical.

"I'm not here to debate the press," the judge told him.

Breen decided to adjourn his official decision until Friday. And so Smith, who made the trip with his new wife Cheryl and other relatives, continues to wait. In South Carolina, Smith and his wife live with children ages 14, 15 and 17.

He said he would be happy to allow his daughter's foster family to visit with the child. He met with his girl Tuesday in a Warren County office, the foster family present. At the meeting, his daughter -- who knows him as "Johnny" -- said at one point about the Smiths, "These are not my family."

Smith said he was crushed by his girl's words. "Who am I then?" he asked. "I'm kind of tired of being left out. Until I get an exact date and got her in my hands, I still have that unusual feeling that something is going to be left out, something is going to be forgotten."

Reach Robert Gavin at 434-2403 or rgavin@timesunion.com

Source: Albany Times Union

Father's fight nearly over, with court returning daughter

Transition from N.Y. foster family not yet set

Editor's note: This is a follow-up to a six-part series of in-depth reports by columnist Issac J. Bailey in which he examined a Conway father's two-year struggle to bring his daughter home from a New York foster home.

After more than two years of fighting, of draining his savings and retirement accounts, of 17-hour drives to New York, Johnny Smith will be bringing his daughter home.

Now it's just a question of when.

But while the legal process is coming to an end, an emotionally tricky transition for Smith's now 5-year-old daughter is just beginning, a transition created by the length of the case.

A judge in Warren County, N.Y., ruled Wednesday morning that the girl, who has been in New York foster care since July 2008 after she was found alone on a busy highway in a diaper and T-shirt, be returned to Smith.

Her mother, Helen Prince, Smith's former common-law wife, had taken her without Smith's knowledge to New York in 2008. There, the teenage sons of Prince's then-boyfriend assaulted the child, who was 3 at the time, according to police and court documents. Prince served almost a year in jail for her role.

"It feels pretty good," Smith said after the ruling. "I'm about wiped out. I just want this to end."

He's happy, but remains leery. He's gotten his hopes up several times over the past two years only to have something work against him.

His attempts to stop what he correctly believed was the abuse of his daughter before she was taken to New York were not followed up by two agencies he approached for help. His pleas over the past two years to allow his daughter to come home during the holidays went unheeded. Even as he inched ever closer to bankruptcy trying to navigate a complicated system, the slow mechanics of a 50-year-old law he couldn't legally challenge ground on.

There were moments during the past two years he considered giving up. But he didn't want his daughter to grow up believing her father didn't do everything he could to bring her home.

"I don't want nothing else to fall through the cracks," he said. "They still had some paperwork missing even today."

His wife, Cheryl Smith, added: "You want to jump up and down, but you get your hopes up a little and something else happens."

Timing of return uncertain

The family had gone into the hearing expecting a fight. The Warren County Department of Social Services had filed documents with the court that argued the girl should remain in foster care because "all of her medical, educational, mental health and emotional needs are being met."

But at the start of the hearing, a Warren County DSS lawyer said the department was not going to oppose Smith's custody petition.

Warren County Family Court Judge Timothy J. Breen didn't comment on the length of the process, the mistakes made, or render an opinion about how S.C. and New York officials handled the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children federal law.

The way that law was enforced is at the heart of the case and its protracted resolution, and the compact is under review for possible change by S.C. officials and child advocates nationally.

While expressing sympathy, Breen told the Smiths "the transition may not be an immediate one."

Another hearing Friday will determine how and how soon the girl's transition home will take place. She could be released into Smith's custody as early as Friday or as late as the Christmas holiday season. Warren County DSS said if she was to be returned home, it should be near the end of the year when there is a natural school break, according to pre-hearing documents.

The judge hinted at a Thanksgiving homecoming.

Smith wants his daughter to come home Friday. She can be back in an Horry County school Monday, he said.

A psychiatrist, counselor and other services have already been arranged for what he knows won't be an easy adjustment for a daughter who has been almost 900 miles from home for roughly 40 percent of her young life. The S.C. Department of Social Services has also said it will help make the transition a successful one.

Such a transition is delicate, said Jim Rogers, a local parenting expert. Children in such situations are at risk for attachment disorders.

"She was so young when she went through all the worst part [of the abuse] that what she will most likely remember is the trauma, the pain, the feelings of helplessness and abandonment, like no one [was] protecting her or nurturing her or comforting her against the world," Rogers said.

"She probably won't remember who did and didn't do what; she will just have the pain," he said. "The little girl's tragic life was caused by other dysfunctional and ignorant parties and made worse by a procedural dragging of the feet."

Dealing with adjustment

Smith has already experienced the reality of the emotional hurdle his daughter faces.

She played with a Fairy Princess Barbie and coloring books during a two-hour supervised visit with the Smiths and an aunt and uncle the day before Wednesday's hearing. The first half of the visit went well, then something unexpected happened.

The Warren County DSS worker supervising the visit told Smith's daughter to "take pictures of your family" with the small camera phone her stepmother allowed her to play with.

"That's not my family," she said. Her father heard her, as did everyone in the room.

"It just really hurt [Johnny] a lot," said stepmom Cheryl Smith. "We were all just sitting there real quiet. We know she is confused."

That's why Smith said he and his wife pre-arranged for a psychiatrist in Horry County to help his daughter deal not only with the transition from foster care back into the home where she lived the first three years of her life without incident, but also with the emotional trauma associated with the assault and injuries she sustained as a 3-year-old.

At the hearing Friday morning, the New York psychiatrist who has been working with Smith's daughter will give her recommendation about the best way for the 5-year-old to be transitioned back to Horry County.

The Smiths told the judge they would welcome contact - through e-mail and calls and visits - between their daughter and the foster family she has known since 2008.

The psychiatrist's recommendations at Friday's hearing also help determine what kind or how much contact Prince, her birth mother, will have with her daughter. Prince has declined to be interviewed for articles on the case.

"You have to be patient," Cheryl Smith said. "With any 5-year-old, you have to be patient. There really is nothing else you can do than show her you love her. And a lot of prayer.

"There may be trying times. We just have to work through them together and love her through it."

Source: Myrtle Beach Sun News

A father's fight | After two years, girl safe in her dad's arms once more

CONWAY -- Johnny Smith pitched a party Saturday at his home in a rural section near Conway to celebrate the homecoming of his daughter and to thank friends and relatives who helped him through his struggle to have her returned to his care.

The child's obvious enjoyment of the gathering belied the trauma she suffered following the breakup of a nine-year live-in relationship between her father and Helen Prince.

After being attacked and abused while in New York, then taken from her mother and placed in a foster home for two years, the child arrived back at the Smith home early on Nov. 5.

Last Monday, Johnny Smith and his wife, Cheryl, whom he wed just over two years ago, enrolled the child in kindergarten - where Cheryl said the child is adapting well and receiving good reports from her teacher.

When asked if she liked her new surroundings, the girlshyly nodded "yes." But before dashing off to get acquainted with cousins and other kin who gathered for the party, she said her favorite thing about kindergarten was the frozen treats she gets there.

"I really like the red and green slushies," she said with a big smile.

The Sun News is not naming the child because she is a victim of abuse, but the family gave permission to use her image.

Relatives that included grandparents from both Smith's and Prince's families gave the child hugs and kisses as Smith grilled hamburgers and hot dogs to feed the welcoming crowd.

"Just seeing her playing means all the world to me," Johnny Smith said as two dozen beef patties sizzled on his grill. "I'm just tickled to death to have her home. Now I just have to work out all the bills that have piled up. If I can just get through the holidays, I'll be one happy fellow."

Nearby, the child's 90-year-old great-grandmother, Lila Roberts, smiled as she sat in her wheelchair and watched the girl running about the yard with cousins who'd gathered for the reunion.

"I'm so glad I don't know what to do," Roberts said. "I had hoped that I'd live long enough to see it. Just look at her. She hasn't met a stranger yet."

The scene was a far cry from the day in July 2008, when two motorists found the then-3-year-old child wandering alone on busy Route 9 in Queensbury, N.Y., and called authorities. Unbeknownst to Smith, Prince had taken the child to Warren County, N.Y., after their live-in relationship ended and she started a relationship with a new boyfriend in Conway.

Clad in a shirt and diaper, the child had gotten away from the hotel room in which she was staying with Prince and the sons of her new boyfriend. The child had been brutally attacked and sexually abused by those boys and, according to court documents, the boys told police they began abusing the child in Conway, then continued the abuse in New York.

After Smith's protracted struggle to bring his daughter back to South Carolina, a Warren County court judge last month granted him and his new wife full custody of the 5-year-old girl. The judge also ruled that Prince could have therapeutic visits with the girl while in the presence of a psychiatrist.

"It was two in the morning last Friday when we got back home," Cheryl Smith said.

"She was asleep so I put her to bed, then I went to bed myself because I had to work the next morning."

She's employed as a shift manager at a Socastee sandwich shop, she said. Johnny Smith said he's looking for a job after being laid off by a tractor firm for which he worked 10 years and another job he had landed servicing mechanical equipment with a restoration firm.

Advocates for change say Smith's case underscores problems in the Interstate Compact for the Placement of Children.

South Carolina legislators plan to consider changes to the law during the next session of the General Assembly. And S.C. DSS officials have already started rethinking how they implement the law.

After The Sun News published the story about his struggles, several Grand Strand residents donated money to help offset Smith's expenses, volunteered free legal help and a neighborhood "adopted" the family through the upcoming holiday season to provide gifts and other necessities.

Source: Myrtle Beach Sun News