Family, Valued

Same-sex marriages have been valid in Ontario since 2003, but not many people know that it had already been legal for a few years to adopt children together as a gay couple. Following a series of court decisions, Paul Farrell and David Smagata became the first same-sex couple in Canada to jointly adopt a child in 2000, via the Children's Aid Society of Toronto. Since then, more than a hundred LGBT Toronto couples have welcomed children into their homes via adoption—a dream that some had grown up believing would never be realized in their lifetimes.

There are three types of adoption, but only two are available to same-sex couples. International adoption is out, since there are currently no countries in the world that will allow a non-resident same-sex couple to jointly adopt. The remaining options are private adoption, where couples apply to a birth mother and she chooses with whom her child is placed, or public adoption, where the available children have become wards of the province and the biological parents have been stripped of their rights to the child. Adopting publicly through one of Toronto's Children's Aid Societies is the most popular non-biological method for LGBT couples—and it's also free.

The Children's Aid Society of Toronto is the largest of the public agencies, and has placed approximately seventy-five children with same-sex parents since 2001. Jewish Family & Child Service and Native Child and Family Services are much smaller organizations, but will place kids into qualified homes run by LGBT parents (the Catholic Children's Aid Society of Toronto did not respond to repeated requests for comment, but the Vatican is vehemently opposed to same-sex adoption).

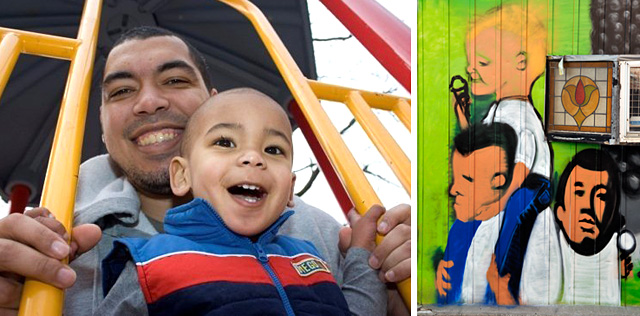

Celebrating family diversity in the windows of the Children's Aid Society of Toronto.

If you walk by Toronto CAS headquarters on Isabella Street this month, you'll notice that the agency heavily campaigns in the LGBT community, and they make no bones about it. "We are open to everyone adopting who can meet the needs of our children," says spokesperson Catherine Snoddon. "This inclusive approach to the idea of family means that people adopting might not necessarily look like the traditional, nuclear family. Children often need different things—sometimes a child may have had a particular challenge attaching to two parents or to a specific gender."

Benita Friedlander of Jewish Family & Child agrees. "The foremost important issue is a match that would be in the child's interest."

Klaudia Meier is one woman who felt she had strikes against her in her quest to adopt a child. "I've always wanted to be a parent, and I've always envisioned doing it on my own," Meier told us. "When you adopt as a single parent, they look particularly hard at your background. I don't have biological family here in Canada, so for the Children's Aid, I had to explain how I would create a supportive community—my family here."

And then, this spring, little Luka was placed in Meier's home. She's realistic about the possibility of encountering ignorance as her son grows up. "Since I'm single, a lot of people don't see that I'm a queer parent, but when Luka starts going to day care or school, it might be an issue."

Though the process to adopt publicly is the same for anyone, black and black-biracial couples tend to have an advantage since those cultures tend not to traditionally adopt and because there are kids in the system waiting for permanent homes right now. An ethnic and cultural match is an important consideration for placement, and some couples find themselves fast-tracked through the process.

Cory Kirkland and his husband added a son to their family in August. "Being a bi-racial couple definitely helped the process," he notes. "The Toronto CAS were sending us prospective matches like crazy."

Differing ethnicities is a consideration for the parents as well. Cultural history and tradition is crucial for the development of a child's identity, just as identification with the LGBT parenting community may be for the parent. "In our case, we're two white women raising a black child," explains Shana Malinsky, who is raising a son with her wife, Kathryn. "That freaks people out more than two lesbians raising a child. There's still a fear out there, but it's more ignorance than negativity; a lack of understanding."

When coming to terms with her sexual identity, Malinsky never really considered that same-sex couples would be able to have children. "I got married to my [male] best friend in high school, because that's what people did—you get married, you have kids, and if you happen to be a lesbian, perhaps even a divorce later on. When I saw that gay marriage looked like it was going to be a reality, I knew that I would be able to have kids together with a partner."

Despite the fearmongering traditionally employed by opponents of LGBT adoption, current research does not support claims that children do better with both a male and female parent. "The important thing is having the components of being a good parent and/or the willingness to learn," says Catherine Snoddon, "irrespective of sexual orientation."

The notion that a child deserves a male and a female parent is a view that makes LGBT parents bristle. Cory Kirkland brings up his own experience. "I grew up mostly under the care of a single mother, and I was always provided for. I had a great childhood."

When asked about role models for her son, Meier is emphatic: "I have a lot of great men in my life, and he gets what he needs from them."

"Comments slip out when people don't think about what they are saying," adds Kirkland. "People ask, 'Aren't you worried he will turn out gay?' or they say, 'Every child should have a mother.' When I mentioned that I planned to adopt some day, I even had a co-worker tell me to my face that she had no problem with gay people, but they should never be allowed to adopt because it harms the child."

It's a belief that's more prevalent south of the border where the rhetoric is more pronounced, yet three decades of solid research doesn't bear it out. Virtually every current credible study has concluded that the ability to parent is irrelevant to the parent's sexual orientation, and according to the Williams Institute in California, there are already sixty-five thousand American children living with gay adoptive parents (most are biological children of one of the parents), and 3% of foster children in the U.S. are living with same-sex foster parents [PDF].

The increased visibility of LGBT adoption has not only helped dull the edges of controversy, but it has also helped prospective parents consider public adoption as a viable option. In the last four years, the Children's Aid Society of Toronto has seen a 12% increase in placements to LGBT families.

"We believe that every child deserves a permanent, loving family," says Snoddon. "When children can't live with their biological parents for whatever reason, finding a new family through adoption becomes paramount. Generally speaking, we have found Toronto's LGBT community to be very receptive to our need for families and have often found members from this community prepared to match the needs of our children."

All photos by Marc Lostracco/Torontoist.

Marc Lostracco was adopted through the Catholic Children's Aid Society of Hamilton, and has an adopted son via the Children's Aid Society of Toronto.

Source: Torontoist