help

collapse

Press one of the expand buttons to see the full text of an article. Later press collapse to revert to the original form. The buttons below expand or collapse all articles.

expand

collapse

Canada's child-welfare crisis

The National Post has investigated Canada's child protection agencies. The first article looks at the problems focusing on Isaiah Wilson, a child born with a genetic defect and threatened by CCAS because of an archaic police report.

expand

collapse

Secretive and often overzealous care agencies protect children largely at parents’ expense

Tara Wilson has been fighting Catholic Children's Aid's involvement with her 10-year-old, special needs son Isaiah in Toronto.

Tara Wilson has been fighting Catholic Children's Aid's involvement with her 10-year-old, special needs son Isaiah in Toronto.Isaiah Wilson acts out — his hyperactivity, in the form of hitting, punching and screaming, a symptom of a rare chromosome deletion called 8P syndrome. Combined with ADHD and autism, the 10-year-old has had a tough life but, thankfully, a loving family.

Three years ago, Tara and Tyrone Wilson brought their son to a downtown Toronto hospital where he was kept for observation. The doctor, a psychiatrist, recommended the Wilsons consider placing Isaiah in a residential home, which would give him more structure. The Catholic Children’s Aid Society would help them through it. They were reassured child welfare involvement would be voluntary.

After mulling this for six months, the Wilsons finally agreed, feeling it would be in Isaiah’s best interests.

Their son, then eight, went to spend his weekdays at a residential facility in nearby Pickering. After much improvement in a month, he came home. A CCAS worker, whom Ms. Wilson said she “treated like family,” continued to visit the Wilsons on a monthly basis.

One day, the worker announced the family’s file would be closed. But then, a week later, she returned to tell the Wilsons that not only would their file remain open, the CCAS was apprehending Isaiah and his parents would have to go to court to get him back. The reason? Isaiah wasn’t making adequate progress at home.

“I was sick to death, in tears, devastated,” Ms. Wilson said. “I thought, ‘This doesn’t make sense.’”

Ms. Wilson convinced the CCAS to keep the file open and have Isaiah remain at home, but her trust in the agency was shattered. So she started writing letters: First to the Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services, then the Child and Family Services Review Board; then the Ontario Child and Youth Advocate and the Ombudsman of Ontario, even though the ombudsman has no jurisdiction over child protection in the province.

“I got a lot of responses,” she said. “But the one that made me seek further legal advice was from the ombudsman.”

The ombudsman’s office asked the CCAS for an explanation — and the one it received came as a shock to Ms. Wilson.

“They told me ‘Tara, they’ve come back saying the reason why they’re taking child away is they do have child protection concerns,’”— concerns they could only trace back to one domestic call to police in which no charges were laid, said Ms. Wilson, who deemed the incident from years ago “silly.” Why, if this was such a concern, was it never mentioned? Why was Ms. Wilson previously allowed to voluntarily take Isaiah out of the treatment home and back into her care? Why would the CCAS worker insist, when she sat in on school meetings, that she was merely there to support the family?

Child protection agencies have sweeping powers in Canada —powers that, in many aspects, span wider than police. And just as sweeping in many jurisdictions is the privacy under which child protection agencies and government ministries operate. It’s a realm where freedom of information laws do not apply. It’s a space of many secrets.

As last year’s Postmedia investigation into deaths in Alberta foster care revealed, a provincial law will not allow parents of children who’ve died in care to speak their names. Ontario has just given investigative powers into such cases to an independent body, but it doesn’t cover parental complaints. While governments insist the wide-sweeping privacy is to protect the best interests of the child, a growing number of families and critics say it is really a way for governments to protect themselves. Parents who feel child protection agencies overstepped their bounds have no place to go but down government-supported roads they feel are not impartial or accountable enough.

“For such a long time, the government has used privacy as a rationale for secrecy and the two are not the same thing,” said Rachel Notley, leader of Alberta’s NDP and former critic of the province’s Ministry of Human Services.

In all other provinces and in the Yukon territory, either an ombudsman or a child advocate hears complaints from parents and has the power to investigate (after a decade of lobbying, Nunavut appointed its first child and youth representative in January).

John Lucas/Postmedia

John Lucas/PostmediaOntario has long been the holdout — the only province in which child protection is not administered by the government directly, but by 51 arm’s length agencies. That has changed this month in the form of Bill 8 — a sweeping accountability measure introduced by the government in response to previous scandals. The bill, which passed into law Tuesday, gives investigative powers to the Ontario Child and Youth Advocate. It should be a massive win, but critics say it doesn’t help parents in the least.

“It’s just smoke in mirrors,” said Neil Haskett, an activist with the Ontario Coalition for Accountability, which has been fighting for child protection since 2006.

He represents a group of parents who feel spurned by the province’s Children’s Aid Societies, alleging they’ve been lied to by workers about their motivations for involvement, that their children have been hurt in care, that their files aren’t being dealt with in a timely manner and that critical information is withheld. The Facebook group he administers is called “Stop the Children’s Aid Society from taking Children from Good Parents.”

When he first saw the title of Bill 8 — “An Act to promote public sector and MPP accountability and transparency” — he thought ‘Wow, that sounds fantastic — accountability may be truly on the horizon.’” But the expanded oversight does not include access to freedom of information requests, it doesn’t give the Advocate power to drop in on a foster home unannounced, it does not allow him to discover abuse in care. It doesn’t go far enough, he said.

“Kids are still going to die. Kids are still going to be abused in care. There’s going to be no way to find the systemic problems that are leading to these issues and why they’re not getting resolved…Families are going to continue to be torn apart.”

Even academics who study the system in Canada share worries about what’s often considered overzealous privacy.

“Sometimes concerns about lack of transparency are quite legitimate. There’s a tendency to not be as accountable to the community,” said Brad McKenzie, a professor of social work at the University of Manitoba.

The secretive nature may also breed distrust; as stories from the parents in Mr. Haskett’s network lay bare, parents feel like the enemy in an adversarial relationship.

“If someone took your kids, you’d be angry too,” said Mary Ballantyne, the executive director of the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies. The society’s job, she stressed, is to protect the child, and while they try to do that with the cooperation of the parents, that is not always possible.

Since assuming office in 2005, Ontario’s ombudsman André Marin has pushed for child protection agencies to come under his umbrella. His office keeps a tally of complaints it received but has no mandate to pursue. Last year, he received 536 — far more than the pervious year’s tally of 472. Between April and November 2014, 290 complaints have filtered in.

“This is serious stuff: Failure to investigate abuse allegations, denial of access to children in care. These people have no place to go,” he told the National Post. “The Children’s Aid Society is funded to the tune of $1.4 billion. That’s a lot of public funds.”

Aaron Vincent Elkaim/CP

Aaron Vincent Elkaim/CPMr. Marin has said he will support Ontario Child and Youth Advocate Irwin Elman in his new investigative role. It is unclear whether he will continue to accept complaints from parents. Mr. Elman won’t. His mandate is, and always has been, speaking up for children.

The Child and Family Services Board — a recent creation designed to address concerns in Ontario — cannot investigate a matter that’s before the courts, and acts as a bureaucratic mediator that ensures protocol was followed. The auditor general looks out for the money. The coroner takes complaints about child deaths, but there is no child death review system in Ontario. Late last month, high-profile pediatrician and child abuse expert Dr. Lionel Dibden resigned from Alberta’s quasi-independent committee to improve the province’s internal death review system, saying the council has been “unable to fulfill its mandate.”

In late November, the Minister for Child and Youth Services rejected Mr. Elman’s plea to extend his powers to protect all the children under his mandate, provide whistleblower protection and give him access to information, saying it would create too much of a ‘document process.’”

“How can I explain to a child or youth who bravely comes forward with a concern about their safety or care that I’m unable to act because the government is concerned about paperwork?” he asked.

Change is occurring in Alberta: Late last month, the province “lifted the veil of secrecy” over the deaths of children in care, promising to make publicly available key details of all deaths. The results come after a damning six-year-long Calgary Herald/Edmonton Journal report on child deaths. Over the past 15 years in Alberta 767 children have died in care.

Alberta mother Velvet Martin is one of two parents legally allowed to speak about her daughter. Samantha, apprehended due to a rare chromosome disorder (not unlike Isaiah) that authorities felt meant her parents couldn’t provide adequate care, suffered multiple injuries and neglect in her foster home and died as a result in 2006 at age 13.

“The entire premise is to protect the child and to protect the family of the child. This is how I was successful in arguing my case in lifting the ban: ‘Well my child doesn’t require protection any longer. She was failed. She is dead,’ ” Ms. Martin said.

This Dec. 3 marked eight years since Samantha passed away in care. Ms. Martin, champion of Samantha’s Law and founder of the organization Protecting Canadian Children, received a human rights award last week for her activism — an award she believes is “owed” to her daughter. “I’m afraid the true picture of what actually exists remains grim,” she said.

In the case of Isaiah and his family, Ms. Wilson feels the CCAS unjustly threatened to take her child from a very good home with loving parents.

She quit her job at the Royal Bank to stay home with him full time and ensure he had as much support as he could get at home.

She ended up spending $25,000 on a lawyer who finally convinced the CCAS to close her son’s file. Her lawyer, Gene Colman, is convinced the file was kept open to ensure the organization got proper funding.

The CCAS declined to comment on Ms. Wilson’s case directly, citing privacy legislation, but said the agency has an informal and formal complaints process and tries its best to resolve complaints with the family. Louise Galego, child protection manager of the Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Toronto, said it is odd that a worker would appear to be closing a file one week and then return the next with an apprehension order.

Ms. Wilson just wants her story told: “I’m not going to smack anybody’s hands or get anybody in trouble. Whatever happened, happened. But someone needs to be held accountable.”

Source: National Post

Next a survey of the inquiries and official reports that have recommended changes to child protection.

expand

collapse

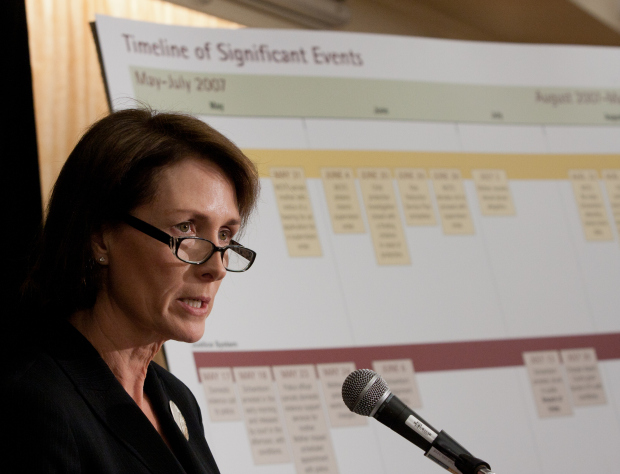

Canada’s child-welfare crisis brings calls for reform from across the country

Katelynn Sampson is pictured in the cafeteria of her school in this April 2008 photo. In 2012, four years after Katelynn died of septic shock brought on by a relentless series of beatings and neglect, Donna Irving, 33, and Warren Johnson, 50, were each given life sentences after pleading guilty to second-degree murder.

Katelynn Sampson is pictured in the cafeteria of her school in this April 2008 photo. In 2012, four years after Katelynn died of septic shock brought on by a relentless series of beatings and neglect, Donna Irving, 33, and Warren Johnson, 50, were each given life sentences after pleading guilty to second-degree murder.The public’s attention and official scrutiny have rarely been so aligned and focused on Canada’s child-welfare crisis. Could this finally be the time for meaningful reform? First in an in-depth series by Sarah Boesveld and Adrian Humphreys:

Sometime in the new year an inquest is expected to probe the hideous death of Katelynn Sampson, a seven-year-old Toronto girl found dead, injured from head-to-toe while in the custody of legal guardians, just as 2014 began with the inquiry report into the death of Phoenix Sinclair, a five-year-old Winnipeg girl who died after she was returned to her abusive mother, and 2013 closed with sickening testimony at the inquest for Jeffrey Baldwin, a five-year-old Toronto boy placed in the care of his grandparents and dying a torturous death.

It is a grim cycle.

Each year bring its own examination of heartbreaking tragedy and a search for answers after a child under state supervision meets a brutish end.

Each case demands wide attention and wrings an emotional response to vulnerable and valuable creatures expiring under the auspices of child welfare authorities, the agencies meant as the antidote to problem parenting.

Each highlights its own nuance and circumstance, often conflicting with the next sad case, and each highlights the infuriating conundrums of child welfare and its stark inadequacies — gaps leaving death review panels as arbiters of how the system is faring, clearly offering answers too late for the doomed children.

“The same concerns about child welfare exist in all provinces. The system’s been the same for at least the past 100 years,” said Irwin Elman, Ontario’s Child and Youth Advocate.

Alongside the headline-grabbing cases, however, something else is happening in Canada, making less of a clamour but also reaching for more satisfying answers.

Ontario is pushing the province’s children’s aid societies to be more transparent and accountable, with parents demanding expanded oversight.

In Alberta, a media investigation revealed the enormous number of children who have quietly died in care and, in response, the government is lifting the veil of secrecy hiding the system from scrutiny and promising reform.

Manitoba has been pressured by the Phoenix inquiry to push aboriginal child welfare onto the national agenda. This summer’s death of Tina Fontaine — a 15-year-old First Nations girl who was molested, killed and dumped in Winnipeg’s Red River within a month of entering foster care — has brought another promise of an overhaul.

Handout/CP

Handout/CPIn Quebec, following a horrific “honour killing” of three teenage girls by their Afghan father, there is a push to better balance culture sensitivity with awareness of unique dangers within diverse ethnic communities.

A damning report in B.C. by the province’s Representative for Children and Youth pilloried the Ministry of Children and Family Development for spending $66 million on merely “talking” about the problems of aboriginal child without “a single child being actually served.”

In Newfoundland and Labrador, the government fought to keep secret a consultant’s report on mishandling child removals. The report, finally made public in March by court order, chided the system’s inability to handle complex cases.

Nationally, there is a call for more focus on addressing long-term risks to children and an epic battle before the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal is demanding equal funding for First Nations child welfare as non-Native children receive.

The public’s attention and official and activist scrutiny have rarely been so aligned and so focused on the disparate strands of Canada’s child welfare crisis.

Could this be the time for meaningful reform?

“I think we’re seeing rumblings of change,” said Mr. Elman.

“We’re beginning to think about ‘How do we do this? Are there other ways of doing child protection? How does a child protection system fit in with other services that are supposed to support families?’”

The push is not only coming from outside the system.

“It is definitely a time of change and transformation in wanting to move forward with the best child welfare system possible,” said Mary Ballantyne, Executive Director of the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies.

“Child protection is an art form — it is not an exact science and it is constantly evolving over time, trying to figure out what is good for kids.”

The problem is acute. The most recent figure on the number of children living in out-of-home care is 67,000, reported in an in-depth 2007 study.

Experts, including Nico Trocmé, director of the McGill Centre for Research on Children and Families in Montreal, say the number will not have gone down: “If anything I’d guess it has increased,” Mr. Trocmé said.

Meanwhile, parents facing intervention by child welfare authorities beg that the government look not at statistics but on their specific cases, making vociferous complaints their children were unfairly seized with little way to get them back — unless they spend thousands of dollars on legal action.

One mother, whose name cannot be published to protect the identities of her children, says her son suffered chemical burns all over his body while in foster care. Parents, and even some frontline workers, complain of child protection agency workers lying and displaying other malicious behaviour.

“They have way too much power,” said one former foster mother, who says she was wrongly accused of abusing a child, of Ontario’s Children’s Aid Societies. “There was absolutely no one I could complain to… I was on my own.”

Handout/The Canadian Press

Handout/The Canadian PressChild welfare intervention can bring out the best and the worst in people. It can be exceedingly polarizing, especially for parents who feel social workers have unnecessarily and illegally interfered in their lives.

Every headline of a child abused in care brings another of a child left to languish without intervention. For social workers — who say the vast majority of their work helps innumerable children and families — it is a frustrating reality of their job.

“Do you really want to know?” said Ms. Ballantyne when asked what it is like doing protection work.

“I hear a siren in the middle of the night and I still wake up thinking ‘Oh my God, has something happened to a child on our watch?’ It takes a big toll.

“However, someone has got to watch out for the most vulnerable kids in our society — and they are, because their parents, for some reason or another, have been compromised in their ability to take care of them, so somebody has got to watch out for them.”

In the eyes of Mr. Elman, there can be no more excuses for not taking a serious, sustained and meaningful look at child protection.

“I’m tired of hearing that there shouldn’t be some rigour, control and accountability on the actions a child welfare agency takes in terms of protecting a child,” he said.

“I can’t think of anything more important for somebody to do than to try to decide how to protect a child or whether to remove a child from their family. What more important event could happen in a child’s life? It could be life or death. But even when it’s not life or death, it’s certainly about the quality of life they’ll have as an adult.”

In his final report on Phoenix’s death, Commissioner Ted Hughes noted that blame and shame flows far and wide in such cases.

“The responsibility to protect children cannot fall solely on the shoulders of the child welfare system,” he wrote. “This is a responsibility that belongs to the entire community.”

Source: National Post

How did the Wabaseemoong First Nation stop children's aid from snatching its children? “They stood at the reserve line on tractors with shotguns saying ‘You aren’t coming into our community and taking any more of our children’ ”. Following this rebellion, sounds of children playing returned to the reserve, after several years absence. This article recounts the sad experience of native foster care since the 1960s.

expand

collapse

‘A lost tribe': Child welfare system accused of repeating residential school history, sapping Aboriginal kids from their homes

Homes on the Siksika Nation Reserve in Alberta on pictured in 2009. In 1973, the Siksika First Nation, east of Calgary, became the first band to kick provincial child protection workers off their territory and start their own agency.

Homes on the Siksika Nation Reserve in Alberta on pictured in 2009. In 1973, the Siksika First Nation, east of Calgary, became the first band to kick provincial child protection workers off their territory and start their own agency.Elders from the Wabaseemoong First Nation in north-western Ontario remember the bus that drove around their reserve picking up children and shuttling them to a waiting plane for a 345 kilometre flight north to Sandy Lake, a remote community with no outside road link, except for ice roads built on frozen lakes and rivers during the winter.

“When the planes landed at the dock, families there were told they could come down and pick out a kid,” said Theresa Stevens, executive director of Anishinaabe Abinoojii Family Services, the current child protection provider for Wabaseemoong.

Such mass apprehension of children from troubled Wabaseemoong, including those flights in the 1970s, have been draining the reserve of its youth for decades, until, in 1990, the community had had enough.

A band council resolution was passed: the Children’s Aid Society was forbidden from entering the reserve.

“They stood at the reserve line on tractors with shotguns saying ‘You aren’t coming into our community and taking any more of our children,’ ” said Ms. Stevens.

The situation was desperate: a third of the reserve’s kids were in foster care; the dip in school-age children made teachers redundant.

“From that day forward they’ve assumed more and more control over their children,” said Ms. Stevens.

In that community near the Ontario-Manitoba order, known in English as Whitedog, standoffs and feuds preceded a new sense of stability. Ms. Steven’s agency has been handling child welfare since 2001, and doing it with the province’s approval since 2006.

“We went from having almost 300 children in care to where we are down to just slightly over 100 for that community. And that is huge,” she said.

A Wabaseemoong elder, Eli Carpenter, poignantly told her the difference it has made. One day he was struck by the uplifting sound of children playing; so many kids had been taken it had been years since he had heard that.

“That’s when we finally started to know we were making inroads and changing the tide of what had happened,” said Ms. Stevens.

Wabaseemoong is not yet a place to be pointed to as a universal model of success in tackling the problems of aboriginal child welfare, but it stands as a marker of hope and a portrait of the hard journey native child welfare reform takes.

Today, after the public apologies and restitution over the government’s residential school system, disproportionately high rates of aboriginal child apprehensions continue across Canada.

“There are more First Nation children in care today than during the height of residential schools,” said Shawn Atleo, former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations. “We cannot lose another generation to the mistakes of the past. First Nations are the youngest and fastest growing segment of the population. We are the future. This is about Canada’s future.”

Goyce Kakegamic, a residential school survivor who is now deputy grand chief for the Nishnawbe Aski Nation — covering two-thirds of Ontario in an arc from Quebec to Manitoba — said it is the missing children of today, not just of the past, sapping vitality from native communities.

“So many of our children have been taken away they are like a lost tribe,” Mr. Kakegamic said.

While all child welfare systems in Canada face challenges, the added complexities of aboriginal child welfare bring a seemingly unbearable quandary.

About 15% of kids in care in Canada are aboriginal, despite natives comprising only 3% of the population; children on reserves are close to eight times more likely than other children to be taken into care.

These statistics alone suggest a problem worthy of attention, but they are coupled with studies saying a majority of native child apprehensions are not over allegations of abuse but, rather, concerns of neglect — with serious questions of what role culture and poverty plays in defining neglect.

“The child protection system for aboriginal children and youth is broken,” said John Beaucage, who was the first Aboriginal Advisor to Ontario’s Minister of Children and Youth Services.

“We see the same type of things repeating: aboriginal children taken away from their community, taken away from their culture and usually … these children find themselves, as adults, trying to figure out who they are, where they belong and are somewhat lost.

“We, as a country, have been repeating the same mistakes over and over again.”

Among those mistakes: not doing enough to tackle root causes that lead to legitimate child apprehension; not finding ways of keeping more native children out of state care by ending unnecessary apprehensions; and finding a balance between meeting demands for aboriginal cultural integrity while maintaining critical standards of care.

“If we keep on doing the same old stupid things, we’re not going to see it stop,” said Mr. Beaucage. “We’re going to see it continue to rise without real benefit and without real change.”

In 1955, the federal Indian Act was changed to allow provincial laws to apply on native reserves and the provinces then went into the business of providing aboriginal child welfare services, although funded by Ottawa.

“We had social workers untrained in the experience of First Nations people; they’d walk onto these reserves, see all this poverty and devastation and children from the residential school system — who are now parents — in a lot of trauma and, instead of seeing that for what it was, they removed the kids all over again,” said Cindy Blackstock, the Executive Director of the and an associate professor at the University of Alberta.

Shaughn Butts / Postmedia News

Shaughn Butts / Postmedia NewsThe federal policy ushered in what is referred to now as the “60s Scoop,” when an estimated 20,000 native children were taken for foster care and adoption, primarily into non-aboriginal families in Canada, United States and Europe.

In 1973, the Siksika First Nation, east of Calgary, became the first band to kick provincial child protection workers off their territory and start their own agency. Manitoba bands soon followed.

There are now 108 aboriginal agencies in Canada mandated to handle child welfare services; at least one in every province except Prince Edward Island and with none in the northern territories.

More are on the horizon. In Ontario, for instance, the seven mandated aboriginal children’s aid societies will almost double if six “pre-mandated” agencies gain full authority; two are on the verge of full mandate status.

Meanwhile, the demands to recognize native culture in child welfare are becoming codified.

In Ontario, the Child and Family Services Act was amended in 2006, requiring child protection workers to ask whether a child has Indian status so that it can be taken into account in care decisions.

In Manitoba, where 80% of children in care are aboriginal, the Authorities Act now states that values, customs and traditional communities must be respected in cases involving aboriginal people.

And last year in Nunavut, where the population is mostly Inuit, the Child and Family Services Act was revised to allow interpretation according to Inuit societal values.

Along the way, the federal government has tinkered with funding in a patchwork approach with provinces: Ontario struck the Indian Welfare Agreement in 1965, allowing the province to bill Ottawa for services it provided for First Nations, although at about 93-cents on the dollar. A funding directive covered the rest of Canada from 1991 until 2007 when Ottawa unveiled an Enhanced Funding formula that brought new money to Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Quebec, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia.

All child protection agencies across Canada start their cases based on a range of suspected maltreatment, including physical, sexual or emotional abuse. Increasingly, children are apprehended without evidence of actual maltreatment but, rather, for concern over neglect, substance abuse, lifestyle or living conditions.

That can hit native families particularly hard.

“It is quite heartbreaking,” said Katherine Hensel, a lawyer who has represented First Nations and aboriginal organizations across Canada.

“First Nation families are still experiencing the wrongful taking of their children on spurious grounds. There is still widespread, unnecessary and unwarranted removal of children.

“Many, many loving and perfectly good aboriginal homes don’t meet a province’s standard of requirements for being foster homes. There are different cultural norms on how children should be raised,” said Ms. Hensel.

Practices by many aboriginal people — such as parent-child co-sleeping, shared housing and multi-generational responsibility for childrearing — are often seen in social work as signs of dysfunction.

“If we deem a home to be a good home and a safe place for a child — but it might not meet all the provincial standards — we try to be as flexible and creative as we can,” said Ms. Stevens, from Anishinaabe Abinoojii Family Services.

While such flexibility and creativity may solve short-term problems, Ms. Blackstock wants long-term solutions. Her organization, along with the Assembly of First Nations, filed a complaint with the Canadian Human Rights Commission in 2007 with the aim of prying more money from Ottawa. The complaint says the government discriminates against aboriginal children living on reserves by providing less funding than is available for non-native children.

Ottawa funds child welfare for on-reserve First Nations while the provinces fund child welfare for non-native children. The gap between the two funding models is estimated to be 22%, the hearing heard.

Ottawa fought to quash the case but the tribunal pressed ahead, holding 72 hearing days in Ottawa ending in October. A decision is expected by the spring.

Answers may come from other directions, too.

Mr. Kakegamic was born in Keewaywin First Nation in Northern Ontario and has experienced a spectrum of native life, raised on the land in a traditional lifestyle by his extended family and also placed in a residential school. He is university educated and now responsible for social services for member bands across northern Ontario — most remote, fly-in only reserves with poor infrastructure.

“We don’t need someone with a PhD to come and tell us what the problems are. We know what the problems are. Because they end up in child care, they end up in drugs and alcohol,” he said; feelings of “futurelessness” lead to high youth suicide rates. “It wounded us to our core and sometimes it is hard to move forward when you are wounded.

“But the answers do not all come from Ottawa.

“We need to look at ourselves. We can do more as a community. We can do more as parents… it’s not only more money and more resources.”

He wants to strengthen and expand aboriginal child welfare agencies in his territory and push more resources into prevention and early intervention.

“We have the skill, we have the capacity, we have the experience — now give us the way to help our own people.”

Moving toward aboriginal jurisdiction over child welfare is not a quick fix.

Last year, a joint Edmonton Journal-Calgary Herald investigation found that, proportionately, more children died in the care of an on-reserve Delegated First Nations Agency than in Alberta’s Children and Family Services Agency.

Tyler Anderson / National Post

Tyler Anderson / National PostThe continuing problems of aboriginals in the child welfare system also became a focus in Manitoba with the inquiry into the death of Phoenix Sinclair, a 5-year-old native girl who died in 2005 after abuse in her mother’s home on Fisher River reserve, north of Winnipeg, three months after returning to her mother’s care.

Even after the intense public attention of the inquiry, gaps in native child welfare still invite tragedy, including 15-year-old Tina Fontaine of Sagkeeng First Nation who was in the care of a Child and Family Services agency in Winnipeg and, within a month, her body found sexually abused and wrapped in plastic in the city’s Red River.

Galvanized by another tragedy, the government has announced another round of changes.

Ms. Stevens, from Anishinaabe Abinoojii, said aboriginal agencies have two concurrent goals: “We have a mandate that is both from the government but also from our First Nations. We’re not just in the business of child welfare, we are also in the business of rebuilding our nation by rebuilding our families.”

A year ago, Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, B.C.’s Representative for Children and Youth, released a scathing report on the province’s aboriginal child welfare, calling it a “colossal failure of public policy.” She said the province spent at least $66 million on “talking” about problems “without a single child being actually served.”

Moving toward new aboriginal agencies is part of the adjustment agencies need to make, said Mary Ballantyne, Executive Director of the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies, where the boardroom is decorated by a quotation from Sitting Bull, the Indian chief who led the native resistance at Little Big Horn.

Darren Stone / Postmedia News

Darren Stone / Postmedia News“More and more, there is recognition that we need to find unique solutions in unique community circumstances.

“But we also need to make sure that the kids are OK. Aboriginal parents don’t want their kids in appalling conditions anymore than anybody else wants their kids in appalling conditions.”

Nico Trocmé, director of the McGill Centre for Research on Children and Families in Montreal, said he supports First Nations control over child welfare services—“with one enormous caveat: Simply dumping those services on First Nations communities and not providing the funding and resources needed is not going to change much of anything.”

“It is not going to be a quick and dirty solution,” said Mr. Beaucage, the former Ontario aboriginal advisor. “A lot of governments, they want a solution before the next election. You have to gauge your success by a different timeframe.

“The solution is not measured in months or years but maybe in ten years, or tens of years.”

Source: National Post

Read what happens in family court, mostly from the point of view of the judge. From the bench, the clients look like riff-raff. One father "believes there’s a great conspiracy against him, one that involves his workplace, the CCAS workers, the police and society at large." An exaggeration, maybe, but what do you call a system in which people in uniforms and robes apply the power of the state to separate parents and children?

The article includes a video report from Tara Wilson (mp4).

expand

collapse

Rare look inside secretive family court reveals parents struggling with poverty, addiction and mental illness

The doorway leading to the Ontario Court of Justice Family Court in North York.Tim Fraser for National Post

The doorway leading to the Ontario Court of Justice Family Court in North York.Tim Fraser for National PostThere isn’t a spare seat in this courthouse waiting room on a Wednesday at noon: Multi-generational families sit huddled together, wearing their winter coats. A woman talks on her cellphone, vowing to record her next interaction with the Children’s Aid Society, to have some kind of proof of suspected misdeeds. A man’s hushed argument with a child protection worker escalates: “I’ll make sure to call you if he loses a shoelace,” he says dismissively before turning away. A child, about 6, bolts from his father and veers through the maze of strangers. Dad catches up eventually.

The Hounorable Justices, from left, Robert Spence, Stanley Sherr, and and Geraldine Waldman are see here at the Ontario Court of Justice Family Court in North York.Tim Fraser for National Post

The Hounorable Justices, from left, Robert Spence, Stanley Sherr, and and Geraldine Waldman are see here at the Ontario Court of Justice Family Court in North York.Tim Fraser for National PostIt is routine activity, but the anxiety is palpable. No wonder: their family’s future is held in the hands of the judge within a courtroom they haven’t even entered yet.

Behind the heavy blond wood doors, parents come under the microscope, their circumstances studied and abilities analyzed in order to determine whether their child is safe in their care or better off in the system.

But the eventual interactions with these judges and lawyers at 47 Sheppard Avenue East in Toronto feel less like a cross-examination and more like a conference with a concerned, yet understanding elder.

The judges try to alleviate the natural tension, to help parents reduce or eliminate risks. Yet they won’t budge if a child’s safety seems imperiled. The law is their guide.

Because family courts are private, the public knows very little about what goes on inside, unless they’re themselves involved. And yet the courts play a critical role in the child protection system — deciding custody matters, assessing risk, recommending resources that may help a family stay intact.

The National Post was given rare access to this court for one day — a day that provides a snapshot of the unique challenges and the powerful impact that good judges can make. The names of the parents who appeared in court that day have been changed in compliance with Child and Family Services Act of Ontario provisions. This is their experience.

“Most families who get involved with Children’s Aid never come to court,” says Justice Stanley Sherr, who represented families in child protection matters for 25 years as a lawyer before becoming a judge. Cases only get here when a “protection application” is filed, usually after a family refuses to voluntarily work with the agency, which has concerns that physical, emotional, sexual harm or abandonment of the child has taken place or might. Once there, Children’s Aid Societies have to make a case for why the agency should be involved. Parents need to prove how they’ve made their home safe enough for the child to be returned. Judges make the call.

“The majority of these people are not child abusers,” Justice Sherr says. Most of the time they just need help. Judges here see parents struggling with poverty, addiction issues, mental illness — various things that impact their environment, the way they parent.

The court at 47 Sheppard practices case management — an approach that’s taking hold in urban centres across the province, but isn’t the norm in all family courts in Canada. Specialist judges get to know the families before them and follow cases all the way through.

In a smart, leather-sleeved jacket, her braided hair pulled back, Stella rises when Justice Sherr enters the courtroom. The Children’s Aid Society has reached an impasse with Stella, its lawyer claims, because this mother of three hasn’t allowed the child protection agency contact with her youngest daughter’s daycare.

There are no new concerns, the lawyer says, except for that. Stella’s lawyer says her client hasn’t told the daycare the Children’s Aid Society was involved with the family because she feared “stigmatization.” But a stack of daily reports on the table prove this child is happy and healthy and doing well.

Justice Sherr asks Stella how she’s faring. She beams and thanks him for asking.

“Everything is doing so well, your honour. I start a new job tomorrow.” She is going to go door-to-door trying to convince people to switch energy providers. They joke about how she may one day knock on his door.

“I’m impressed by the improvements you’ve made in your life,” he says. He tells the lawyer to hand the daycare reports over to the CAS lawyer. If they are positive, the CAS will leave Stella alone.

“When that woman first came to court, she was on the ceiling,” Justice Sherr says after the hearing. Back in 2012, her children were apprehended over allegations of physical harm. “There had been broken bones,” Justice Sherr says. The parents blamed each other. Stella was livid. The CAS tried to facilitate temporary custody, but failed. “Then she started the work,” he says, which involved parenting classes and anger management. The court gradually increased her access to a point where the children returned home, one by one.

A courtroom at the Ontario Court of Justice Family Court in North York.Tim Fraser for National Post

A courtroom at the Ontario Court of Justice Family Court in North York.Tim Fraser for National Post“I could justify a supervision order, but sometimes the society’s involvement, at a certain point, can be counterproductive,” he says. In this case, the CAS’s attempt to keep tabs on an otherwise healthy, happy child has the potential to backfire. Over-intervention, he says, carries its own risk.

Stella’s progress through court provides “almost a classic example of how case management can work if you can get the client buying in, the judge buying in and then the lawyers buying in,” he says. “She’s to the point now where she has her children back and maybe we’re close to terminating [CAS involvement].” But it took building a relationship to get there — the winning ingredient. Without that relationship, it’s easy for the court to feel adversarial.

“When you come into child protection court, the dominant emotions we face the most are fear – what’s going to happen to me? What’s going to happen to my family? What’s going to happen to my children?” Justice Sherr says. “The other dominant emotion in child protection is humiliation. It’s tremendously humiliating when your children have been taken away from you. How do you face your family? How do you face your community? Am I that bad a person that the Society has to take away my children?”

In case management, the judge involves the parent in a plan. He had a long talk with Stella and convinced her that he wanted her to succeed. While not everything is perfect, by and large, she has. A few hours after her 10-minute hearing, the CAS came back with the stack of daycare reports. They were willing to end their involvement.

Heather does not want her daughter to come home. It’s not safe there. Not since her father came home a few months back and Heather let him in though she swore she’d never do it again.

“He’s a junkie…he hit me, he broke up my house, I don’t want him around me,” she says, claiming he also blew through $52,000. “Right now I’m messed up and I need to get better,” she says, her voice cracking.

The Children’s Aid lawyer tells court that Heather pulled a knife on her daughter’s father and threatened to stab him 28 times.

“All I want is what’s best for my family,” she says through tears. “The rage I have towards him is unbelievable.”

Justice Geraldine Waldman listens carefully and keeps her gaze fixed to this crying woman before her.

“Are you seeing a doctor?” Justice Waldman asks calmly. Yes, she is, but the pills make her feel like a zombie.

“Does the Children’s Aid have an obligation to call the police?” Justice Waldman asks. The lawyer responds that Heather’s daughter is not in danger. “Oh, I would never hurt my children, I love my children,” Heather cries.

“I think for the moment, your access to your daughter needs to be supervised,” Justice Waldman says. This is not what Heather wants to hear.

She pleads, then resigns herself, then pleads again for unsupervised visits with her daughter.

Justice Waldman is firm that there be no overnight visits. “Our job and the Society’s job is to help make sure your daughter is OK,” Justice Waldman says. “We are worried that when your daughter is there, you can frighten her by your emotions and your behaviour.”

Then, with a simple switch in wording, Justice Waldman changes the tone from despair to relief. “Let’s call the visits ‘managed’ and not ‘supervised’,” she says. The air returns to the room.

“Oh, I like that word better. ‘Managed’,” Heather says. She looks calm now and walks out, still flushed from the emotional rollercoaster.

“You can see how multi-dimensional my job is,” Justice Waldman says when the door behind Heather shuts.

“Mental health, intellectual capacity, immigration, parenting conflict, substance abuse, domestic abuse, systemic poverty,” Justice Waldman lists off the social dimensions she routinely sees. “And in how many of these cases do they say ‘Mom was a crown ward?’” The answer is ‘lots.’ The system has not yet found a way to break the pattern, she says. But by trying to identify the core challenges these families face, they can at least try to ensure these parents get the resources they need to help make them into better parents.

Arjun and Tanvi have been at loggerheads over their daughter for most of her short life. Now they stand before a judge on a summary judgment motion brought by the Catholic Children’s Aid Society, which argues their little girl, who is 5, is in need of protection. The domestic conflict and risk of violence she may be exposed to in her father’s care is too great, court hears, so they are supporting a bid to give Tanvi sole custody.

She wants another chance to keep her family, but acknowledges “not everything is rosy.” She worries he might try to take the child back to India, where the couple had emigrated from a few years before.

There are emerging concerns about Arjun’s mental health, lawyers for the CCAS argue. He believes there’s a great conspiracy against him, one that involves his workplace, the CCAS workers, the police and society at large.

He had also struck Tanvi during an argument, though most of their fights were verbal. And, though he claims innocence, Arjun pleaded guilty to assault because he believed he had a “responsibility” to do so, he says. The major sticking point, Justice Robert Spence points out, is that Arjun refused a court-ordered mental health assessment. The society raises concern that the girl is at risk of emotional harm.

It’s a tortuous back and forth between Justice Spence and Arjun, who gives roundabout non-answers to his questions.

The eventual decision does not play into Arjun’s favour.

“I find that the child was at risk of emotional harm, the high conflict was exacerbated by the father’s behaviour.

“I will leave the child in the custody of the mother,” Justice Spence says. “It’s the least intrusive action as it takes the CCAS out of the equation.”

Tears are pooling in Arjun’s eyes. “No one wants to sever the relationship with your daughter,” Justice Spence tells Arjun, his voice softer than earlier. “You need to find a way to have a normal relationship with your daughter, and there’s things you can do.” Justice Spence wants Arjun to acknowledge his mental health challenges and seek help.

Arjun represented himself in court — a choice many parents make. Had he accepted duty counsel’s help, he may have been quicker to acknowledge the risks and address them sooner. That’s a huge challenge for a lot of parents, because they are resistant to Children’s Aid intervention.

And in the cases of new immigrants, such as Arjun, entering a society with vastly different expectations can be a shock, Justice Sherr says.

“Not only do you have to admit [the risks], you have to get the services, you have to be able to address them,” he says. “You have to show progress.”

The added hurdle is the short window of time you have in which to show progress: Children under six should not be made society wards after one year, the law says, so this means the court needs to decide the child’s future quickly.

Source: National Post